The Sad Poem: Bearing (with) One’s Soul

I have spent days agonizing over this. Now it’s your turn.

“The “danger … of mistaking for the effervescent energy of creative intelligence, that which is only the exuberance of personal ‘feelings unemployed’”

~ Rufus Griswold, Preface to The Female Poets of America, 18481

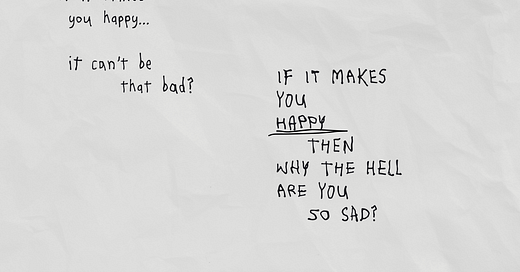

Ah, the “sad poem”. Sadness has been a driving force behind and an ongoing theme in my own poetic practice since my days in a creative writing workshop as a teenager. Those who wrote “sad poems”, detailing the depths of depression and the bleakest of takes on their surroundings always received a different, more genuine kind of praise. Their poems were met with sober silence, rather than raucous applause. It was a type of accolade. Happy poems, angry poems, even funny poems- they did not receive such a serious kind of treatment. While part of the “sad poem” phenomenon I personally experienced owes itself to the dark, kiss-my-scars-2014-Tumblr world within which I spent my writerly youth, I saw the “sad poem” phenomenon in Rufus Griswold’s over 150-year-old denunciation of female poetry. The “sad poem” is, in its purest sense, “personal ‘feelings unemployed’”. Is this characterization of the sad poem just another excuse to discount poetry written by majority AFAB people? My childhood writing workshop was, after all, solidly 80% AFAB. When written by a man, a “sad poem” is genius. When written by a woman they need to suck it up, or perhaps get a therapist.

When I became an older teenager and my funny short stories shifted into “sad poems”, I remember being proud of myself. I had finally grown up. Reading my teenage “sad poems”, Griswold probably would’ve laughed to himself at my pitiful attempts of “affective imitation”. Oh, look at her, trying to think like a boy. She should save those tears for the pillow. It’s quite hilarious to imagine Griswold, in all his self-importance, quoting the notorious Abby Lee Miller. To Griswold, a “sad poem” written by a girl is perhaps the closest a female poet can come to “the effervescent energy of creative intelligence”. In other words, it is the best possible imitation. Well done, girl. That’s cute. Now back to the kitchen.

Still, though, it is the “sad poem” that reigns supreme in poetic circles. It is the “sad poem” that grants little girls legitimacy in their writing workshops, and wins them poetry contests. No matter how good the writer, their “sad poem” will always hit harder; go further than their happier stuff. Only the baring of one’s soul will do. The thing is, baring your soul takes a lot, especially for those (unlike me) who find it hard to share that kind of stuff. I’m happy to let my soul flap in the wind2, and couldn’t wait for my turn to share my first “sad poem” with the writing circle. Yet, the “sad poem” hegemony demands that those who perhaps don’t want to be broadcasting their darkest thoughts to the public feel they should do so to be taken seriously as poets. It rings of the other demands the heteropatriarchy puts on women and queer people: give us everything of yourself, and even then it will probably not be enough. If a little girl isn’t ready (or simply does not want to!) bare the raw parts of her soul to win a poetry contest, she shouldn’t have to; it shouldn’t put her at competitive disadvantage. Unfortunately, that’s not the way the poetry world works. After years of waiting my turn, I had a moment of celebration after being diagnosed with anorexia at the age of 16. Finally, I had been gifted with a real trauma to write about. Wouldn’t you know it, but the first poem I wrote about being anorexic made it into a magazine3.

Does denouncing the sad poem as another one of those darned patriarchal constructions that’s Trojan-horsed their way into the ostensibly feminist writing-workshop space under the guise of “that’s just how things are” do anything? How do we reconcile, as a friend of mine so aptly put it in a text, “the tension [between] ‘sad poems suck’ and ‘women’s sad poetry is less respected than men’s’”? Both can be true at the same time.

Let’s for a moment imagine a wheel. On one side of the rim is painted, “sad poems suck” and on the other is “women’s sad poetry is less respected than men’s”. As the wheel spins around, it gives the illusion that “sad poems suck” is falling into “women’s sad poetry is less respected than men’s”, before emerging again, and falling again until the wheel is spinning so fast that you can’t even read the words on it anymore. Sad poems do kind of suck. Though I was lauded for them (and indeed, lauded my friends for their seminal “sad poems” every Wednesday over a bowl of nutritional-yeast popcorn4 at writing workshop), in retrospect they were a heaping pile of cliche teenage angst. Griswold’s “personal ‘feelings unemployed’”, back at it again. Part of the celebration of “sad poems” at workshop wasn’t for their actual content, but for the knowledge that the people behind the poems were going through unimaginable suffering. Take a quote from Virginia Jackson’s Poet as Poetess: The “transformation of the woman poet from a writer of various verse genres into the figure of the Poetess… exceeded conventions of gender and genre and thus came to represent Poetry” (Jackson, 57). Jackson’s Poetess is not just a woman who writes poems, but symbolic of a certain type of poetry that speaks to deep -and implied, unnecessary- emotion. The Poetess is the platonic ideal of girly poetry. There’s a reason Emily Dickinson, the only female poet in the entirety of the dusty poetic canon you may remember from seventh grade English class, is the Poetess poster-girl. Any poetry not written by a white man is automatically subject to Poetessing; a part of it, no matter how small, becomes inextricably intertwined with the author’s identity. Usually the nonwhite, non-male part. As it turns out, us teenagers camped out on couches and folding chairs in our workshop leader’s living room were doing almost the exact same thing.

My workshop, called Woven Word, was an offshoot of a larger program called Amherst Writers and Artists, and as such followed the same rules they set out for their adult participants. I’m not going to bore you with all of them, but the rule we most often broke (and were thus constantly reminded of) was that during feedback time after someone read their writing aloud, we were not allowed to refer to the narrator of the piece as “you”, even if the person who had just read was someone we knew well and, hell, the thing they’d just described in the piece was something you’d literally been there for. Our modus operandi was, quite literally, to separate the poem from the poet. We were at workshop to craft writing and then speak on that craft. Per our workshop leader’s instructions, we were supposed to “comment on what’s working in the piece”. We did…the exact opposite. Not only did we not even try to replace “you” with “the narrator”, but we actively used what we knew about our writer-friends outside the workshop circle to inform our commentary. At one point, we went as far as to ascribe different styles of poetry to the people who wrote them most often. A short gut-punch with impeccable language was an Ada Poem5 and unsurprisingly, even in the realm of “sad poems”, if it made you laugh, it belonged in Maddie territory.

Like an Ada Poem or a Maddie Poem, a “sad poem” speaks directly to the poet’s identity. If someone shared a “sad poem” at Woven Word, it was a clear message to the others in the circle that they were going through it. It was a way to say “I’m sad” without having to actually form the words. In that regard, letting the author become symbolic of their work (or vice versa) is actually a powerful means of communication. The issue lies in the poem being interpreted only as indicative of its author. A form of Jackson’s Poetessing can be attributed to every sort of poetry written by someone other than a white man. Nonwhite, non-male emotionality is seen as frivolous, maybe even dangerous. Just as nonwhite, non-men are encouraged to leverage their emotionality to get ahead, they are shot down for their incorrect portrayal of white masculinity. Yet it is the white men who set the bar, forcing everyone else to insert themselves into the “sad poem” paradigm, despite knowing it will result in nonwhite, non-male writers being unable to separate their identities from their work. Thus, the “sad poem” is can only be subject to literary criticism based on its content alone if it’s written by a white man. Everyone else is stuck on the merry-go-round.

I want to be very clear when I say this is not me trashing my writing workshop. Though it has been years since I graduated, just the sight of the promotional email has me struck with enough yearning for bygone times that I have to lie down for a little while. Not even the greatest Wednesday night at college could come close to those nights spent in front of the wood stove, swapping worlds across the coffee table. I don’t blame the people we were back then for breaking what in retrospect is an important protocol for literary criticism; I only wish the reasoning behind it had been better explained to us. Like I did for numerous other concepts back then, I just thought the “sad poem” hegemony was the way things were, preferring to anxiously await my turn to write sad instead of questioning why I even needed to have a turn in the first place.

Hailing from Western Massachusetts, it was a given that all of us in Woven Word considered ourselves feminists. Yet as I said before, the worship of the “sad poem” seems to play right into Griswold’s hands. If writing a “sad poem” is a young non-man’s feeble attempt to think like a boy, then the exaltation of “sad poems” is really just boy-worship in disguise. Margaret Atwood’s “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman.”6 does and doesn’t apply to our writing-workshop quandary. On one hand, the exaltation of the “sad poem” is telling of the systems that were actually at play at Woven Word. Despite our attempts to make our writing circle a space outside the heteropatriarchal, “normal” world within which a majority of us were excluded or even bullied outright, we were only reenacting the laws of the “normal” world in a different font. The praise we garnered from sharing a “sad poem”, written ostensibly about the pain of rejection from the “normal world”, was actually rooted in the structures of that world; structures we sought so dearly to contradict. And the wheel keeps rolling.

However, the heteropatriarchy us (majority queer, gender-expansive) writers practiced within our weekly writing circle and the heteropatriarchy the “normal world” practices are not the same animal. While rooted in the same places, they are like comparing apples and, well, worse apples7. One is interesting to dig at in retrospect as to better understand how larger concepts of gender and sexuality enacted themselves within our writing circle. With the other heteropatriarchy, though, the bullying my friends and I experienced was actually a fairly benign consequence of violating its rules, with worse ones including murder. These consequences were only compounded at the intersections of race, class, and gender that my writer friends experienced to varying degrees. The same poetry I read with pride at Woven Word was something I kept a closely guarded secret outside of the writing circle. Not even my own friends at school knew the content of my writing, only that I wrote for two hours at some lady’s house every Wednesday. At my school, (as I’m sure it was at many others), poetry was considered a dumb, frilly thing, only to be done at the behest of an English teacher during some three-week unit. I would never have dreamed of submitting a “sad poem” for my English class, lest one of my bullies catch a glimpse. My “personal feelings unemployed” were not for the likes of anyone outside Woven Word.

As I said above, Tumblr had a lot to do with it. This may surprise all of you, but I have never actually had a Tumblr. As an early teen wanting so desperately to slot myself in beside the rest of the blonde-highlighted North Face vest- wearers at my school, I effectively banned myself from ever making a Tumblr page, interacting with the site through screenshots of popular posts posted to Instagram. Not having a page of my own did not shield me from Tumblr’s overarching influence, and I found myself resonating with the portrait of 2010s Tumblr Princess Babygirl draws up in her essay All Alone in Their White Girl Pain. Tumblr magnified the “sad poem”, turning it from a writing practice to an aesthetic complete with its own dress code and slang. Not only was it important to write “sad poems”, but to be a sad poet. I’m sure the aesthetic comes to mind quickly for some of you: band-aids, the Arctic Monkeys, so on and so forth. It was also racialized as hell, and I take full responsibility that while I actively hid from it, sad-white-girl Tumblr could have been mine had I just had the balls. Many of my writer friends (in my majority-white rural community8) did not have the same qualms about Tumblr and took the whole aesthetic in stride. It wasn’t just about writing the “sad poems”, it was about being the kind of person who wrote sad poems. Look at any of the old Woven Word group pictures and you will see a stark contrast between myself and my fellow writers. While they were experimenting (as teenagers do) with all the trappings of the era: wigs, thick-rimmed glasses, knee socks; I appear in every photo in nearly identical gray sweatshirts and black leggings. Like my writing, my engagement with 2010s Tumblr was a closely guarded secret: while I rattled off “sad poems” with the rest of them, I made it very clear that when the workshop ended, I would return to the “normal world” and blend in seamlessly.

The “sad poem” thus sits in a weird little in-between space. By the metric of “normal world” heteropatriarchy, it is a ridiculous girly thing, written by and for the girls and avoided by the boys completely. 2010s Tumblr is wedged right beside it, as the whole point of popularity within that space was to be as unlike the “other girls” as possible. As we near the halfway point of the 2020s, “not like the other girls” has become a laughable trope, known more for its feeble attempt at disguising patriarchy as feminism than it is for being anything of real substance. With a decade of distance between us and those nutsy hipsters, we can see crystal clear that aestheticizing being unlike other girls is actually just the heteropatriarchy’s attempt to divide and conquer the third-wave feminist front. We know now that being like (and standing with) the other girls is a sign of strength. The “sad poem” is, in a sense, another trapping of the not-like-the-other girls aesthetic: she’s smart, she’s quirky, she writes sad poetry. The very thing the girl-poet does to subvert the male gaze is, in fact, the thing that brings it in. After the writing workshop ends, she’ll bring that poem straight to the One Direction concert, and boy is it gonna reel Harry in.

If we know that acting “not like the other girls” is blatant boy-worship, why is it so hard to extrapolate that the “sad poem” hegemony is too? I mean, it’s beyond me how boys at school couldn’t seem to figure out that the very frilly shit they denounced was in fact just another shrine dedicated to them; it was just stupid because all the girls were doing it. That’s because while the “sad poem” has been absorbed into the murky depths of 2010s sad-girl Tumblr, it is still a real poetic practice. Those boys sure know that now, as they pump out “sad poems” for the sake of attracting women with their deep introspection that is not at all like the other boys. The same stuff they made fun of in eighth grade is now their bread and butter, and now that it’s been disentangled from Tumblr in the oh-so-enlightened 2020s, best believe they are celebrated for it. After all, they’re not imitating anything. Theirs is the real deal.

Two things can be true at the same time: that the “sad poem” can be melodramatic Tumblr-bait drivel only praised for the sake of a reblog, or cheering up a friend who is clearly in some kind of mental distress, and that part of the reason we see “sad poems” as melodramatic drivel is because they have become feminized, especially by way of the Tumblr brigade. We are much less likely to call the same shit melodramatic when it’s written by a man. Some “sad poems” are fantastic. I remember hearing quite a few during my time at Woven Word that shifted my world on its axis. Some were quite melodramatic, but we were teenagers going through a lot of crazy shit. If writing and sharing those poems were what we needed to cope at that moment, I don’t blame us. What I do know now, though, is that those “sad poems” were not inherently deeper or better than poems rooted in any other emotion.

In fact, a happy, nonviolent poem is an act of resistance. Deliberately practicing kindness and positivity (in moderation, not the toxic shit9) despite having experienced the horrors of the world is powerful. It is the heteropatriarchy that tells us we must think like boys to be taken seriously; that we must be sad to produce good work. So I say to all of the writer-girls and budding poets out there, write whatever the hell you want, whenever the feeling strikes you. The most important part of a good poem is authenticity. After explaining the concept of this essay to a friend of mine, they told me that sad poems feel more honest. Perhaps this is the man in their head, or perhaps it is their truth. It might be both. I am not against “sad poems”, only the elevation of them as the best and truest form of poetry. For some people (like my friend), sad poetry feels more honest. For others, that might not be true. What I’m trying to say is write about what you’re really feeling, not just what you think the world wants you to feel. If that happens to be sad, so be it! But don’t make yourself write sad poetry when you’d rather be writing something else. Sadness is not the only thing that creates good poetry. While I don’t foresee the heteropatriarchy retracting its claws from the world of poetry anytime soon, I can say that writing true to yourself and your feelings is a great way to derive joy from writing. Isn’t that what it’s all about?

Jackson, Virginia. “The Poet as Poetess.” The Cambridge Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Poetry. Ed. Kerry Larson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. 54–75. Print. Cambridge Companions to Literature. (Wow! An actual citation.)

The image I want you to think of here is a wind sock. Bright orange.

For those who are curious, it’s called Natalia, and was published in the 2021 edition of Susquehanna University’s The Apprentice Writer.

Ah, the yeast corn. I will forever be a hater.

Ada is a dear friend of mine to this day, and a truly remarkable writer.

Atwood, Margaret, 1939-, The Robber Bride. New York, Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 1993. (Another?! Maddie, you’ve really outdone yourself.)

Think, like, a honeycrisp vs. a mackintosh. Which would you rather sink your teeth into?

In the summers, the whole writing workshop used to pile into the back of a pickup truck and ride down to the river to splash around. Yee-haw!

Hang in there, baby! does not count as poetry.

Wow. This is so deeply insightful. Really made me think about things I hadn’t before. Thank you. Also I love the advice you offer at the end.

i love the example of the wheel that you used! very well written & a great read, thank you for sharing